It is time to Stand up for Science

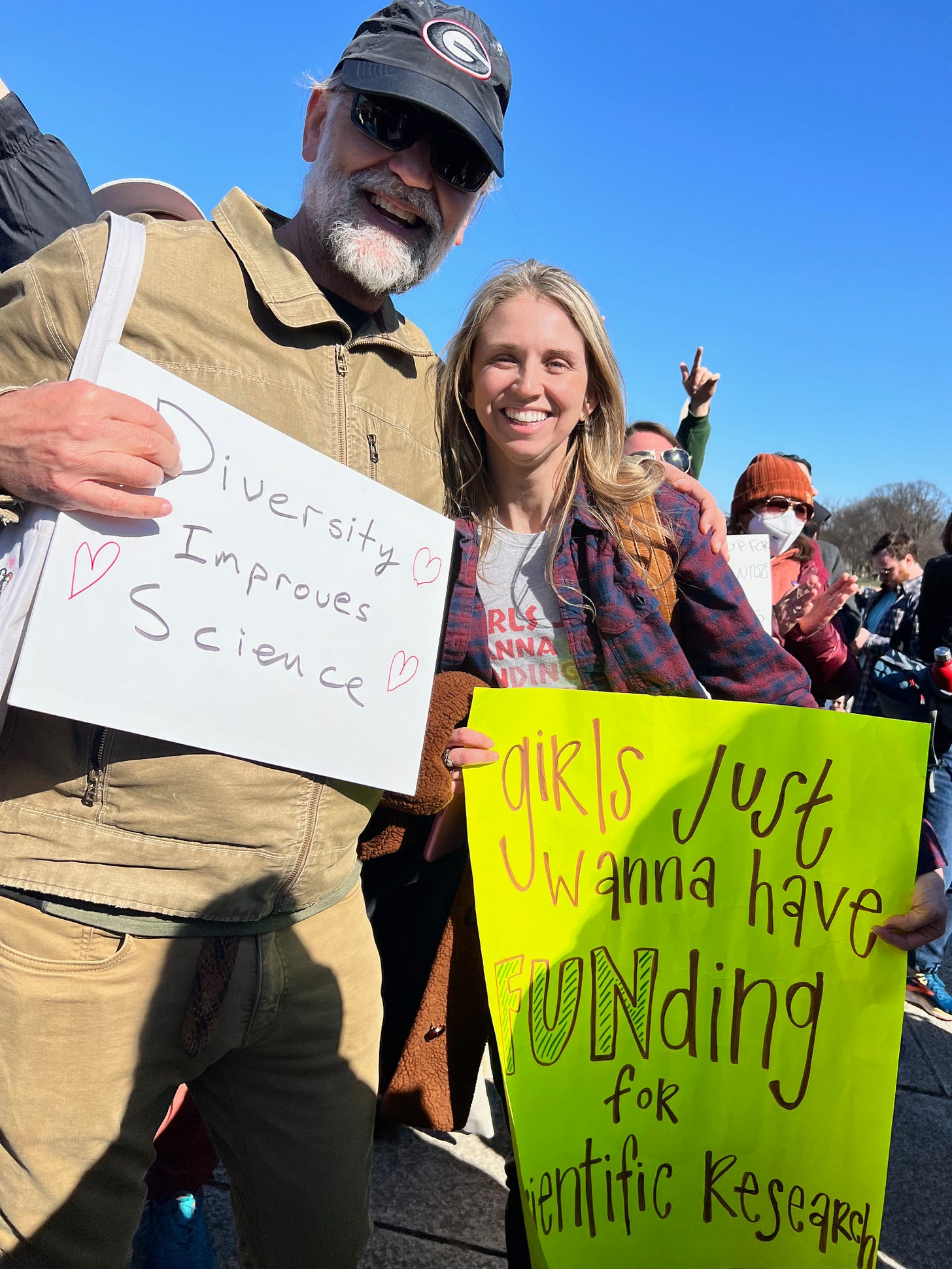

This new substack was motivated by my recent trip to Washington D.C. to join the Stand up for Science rally on March 7.

I’m a university biochemistry professor. I've been doing this job for 29 years and have seen many ups and downs in the lab over the years. I love my job and am an optimist by nature. I think that most scientists are optimists. It is a healthy personality trait, because so much of what we do in the lab does not work as expected. To quote my Ph.D. advisor "If you knew what you were doing, it wouldn't be research" (I've since discovered that most Ph.D. advisors seem to confer the same wisdom...). Scientists need to be excited to try something new if an experiment does not work. When an experiment does work, it is always satisfying, the more so after working on a tough problem for a long time.

In addition to learning how to respond to failed experiments, scientists need to learn to face rejection. The most important currency in academic science is a peer-reviewed publication. Getting a paper accepted into a journal is always a moment of celebration, because it can be the culmination of years of work. The process of getting a paper accepted can be challenging, because the peer-review system is set up to check our work and to ensure that a published paper is supported by good science and strong data. We are driven by data and will often spend months collecting new data to support a hypothesis when reviewers request it. The system isn't perfect, but it is pretty good and usually results in higher quality research.

Another source of rejection is from funding agencies. Running a lab at a university requires outside funding to pay for supplies, personnel, and equipment. It is a lot like running a small business. To get the money to pay for research, professors must write grants, most often to federal funding agencies such as the NIH, NSF, DOE, CDC, DOD, and others. The funding agencies also have peer review, but the process is much slower than publishing a paper. It takes months of work to prepare a grant proposal, and once it is submitted to the funding agency, it takes months to complete the peer review process. When a grant proposal gets rejected, that process usually takes about 1 year, and the optimistic scientist needs to make new plans based on the peer review comments. (Usually, even the optimistic people take a day or two to complain about how unfair it was before we get back to it. And almost always after emotions have cooled down, we usually realize that the reviewers had some good points, and our science gets better as a result.) When a grant gets funded, that is even a bigger celebration for the lab!

Oh, did I mention that research is often only about half of our job? For most of rest of the time we are teaching the next generation of scientists, engineers, physicians, vets, and other professionals. Like many of my colleagues, I love teaching, but it takes a huge amount of time and effort and can add stress to the research part of our job when research funding is tight. The last part of our job is service: helping to run graduate and undergraduate programs, seminar programs, faculty recruiting and mentoring, and many other jobs to keep the department and university working.

To get a tenure-track job as a university professor in a STEM discipline requires at least 8 years of formal education past high school as well as 3-4 years additional training as a postdoctoral researcher. Those 12 years of preparation are comparable to what is required to become a medical doctor. Many scientists today want to go into industry, but the preparation to be head of a group in industry is about the same as a professor job. Most scientists love their jobs, thrive on discovery and the potential for developing new products or knowledge that can help society. The stresses associated with the 12 years of preparation, publication, and grant funding are just part of the job.

Over the past several weeks, the Trump administration has created chaos for university scientists. We have endured threats of freezing grants that have already been awarded, cutting staff at agencies that we rely on for our funding support, cutting off peer review to get new grant proposals evaluated, and significantly reducing the "indirect costs" (IDCs) that our universities get from our grants to pay for upkeep of labs, electricity, staff to help us manage the grants and comply with federal regulations, core equipment support, and much more. Entire programs are being cut, sometimes without warning. This has a real impact, because we must pay the students and staff in our labs who are getting trained to do the research. Some programs are already cutting back on graduate student admissions, undergraduate summer training opportunities, postdoctoral scientist positions, and new faculty recruitment.

Science, especially biomedical research, has historically had bipartisan support. Most of us have been close to people who have had serious diseases such as cancer or Alzheimer's. The NIH supports research into these and other diseases, but the NIH is now threatened by Trump and Musk. The NSF and NIH support basic science that result in a better understanding of the world around us and often to unexpected benefits such as CRISPR technology that has revolutionized our approach to curing genetic disorders but was discovered in bacteria.

Trump and Musk are squandering America's dominance in science and engineering, and as a result, we are already starting to lose a generation of scientists in the US who will not be making the next major discovery to improve human health or add to our economic growth. Someday there will be another pandemic and leaving the WHO and cutting the CDC leave us more vulnerable. And the climate continues to get worse, regardless of what Trump and the GOP believe. It is getting hotter, storms are getting bigger and more destructive, flooding is getting more widespread, and wildfires are burning more acres.

This is not Making America Great Again. It is selling off our future growth and discoveries in a fire sale.

In the essays to follow, I plan on trying to show readers why I love science and to tell stories about some of the many adventures I've been fortunate to have. Please stay tuned!